Advanced Deep Learning - Custom Neural Networks with TensorFlow

In this final part of our series, we’ll explore advanced TensorFlow concepts by building a sophisticated regression model. While Part 2 introduced basic neural networks for classification, we’ll now tackle regression and demonstrate TensorFlow’s powerful features for model customization and optimization. However, as in part 3, the purpose of this tutorial is to highlight the flexibility and capabilities of TensorFlow. Therefore, this showcase is mostly about introducing you to those advanced routines and not about how to create the best regression model.

The complete code for this tutorial can be found in the 04_tensorflow_advanced.py script.

Why Advanced Neural Networks?

Complex real-world problems often require:

- Custom model architectures

- Advanced optimization strategies

- Robust training procedures

- Model performance monitoring

TensorFlow provides all these capabilities, and we’ll learn how to use them effectively.

As always, first, let’s import the scientific Python packages we need.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow import keras

from tensorflow.keras import layers

1. Dataset Preparation

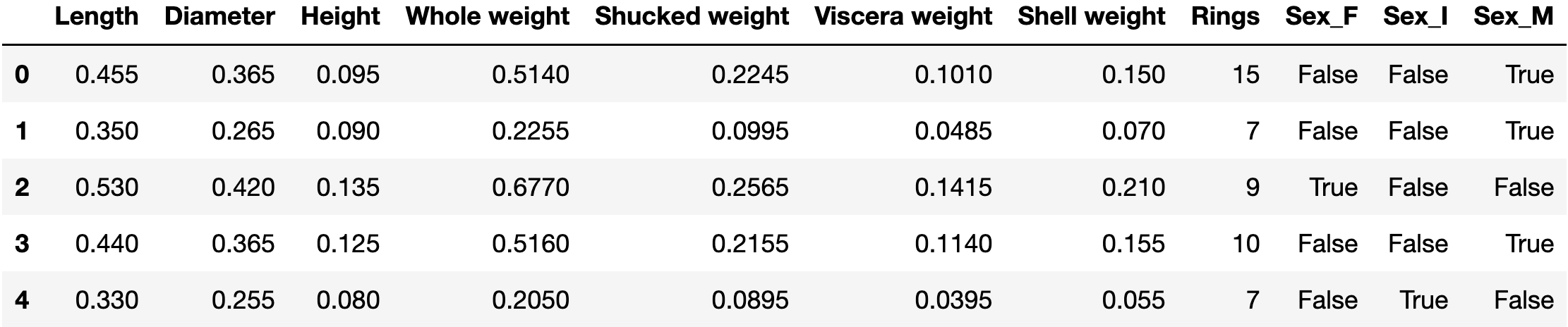

For the regression task we will use a small dataset about abalone marine snails. The dataset contains 8 features from 4177 snails. In our regression task, we will use 7 of these features, to predict the number of rings a snail has (which determines their age).

The abalone dataset is a classic regression problem where we try to predict the age of abalone (sea snails) based on physical measurements. While this might seem niche, it represents common challenges in regression:

- Multiple input features of different types

- A continuous target variable

- Natural variability in the data

- Non-linear relationships between features

So let’s go ahead and bring the data into an appropriate shape.

# Load and prepare dataset

url = 'https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/abalone/abalone.data'

columns = [

'Sex', 'Length', 'Diameter', 'Height', 'Whole weight',

'Shucked weight', 'Viscera weight', 'Shell weight', 'Rings'

]

df = pd.read_csv(url, header=None, names=columns)

# Convert categorical data to numerical

df = pd.get_dummies(df)

print(f"Shape of dataset: {df.shape}")

df.head()

Shape of dataset: (4177, 11)

Next, let’s split the dataset into a train and test set.

# Split dataset into train and test set

df_tr = df.sample(frac=0.8, random_state=0)

df_te = df.drop(df_tr.index)

# Separate target from features and convert to float32

x_tr = np.asarray(df_tr.drop(columns=['Rings'])).astype('float32')

x_te = np.asarray(df_te.drop(columns=['Rings'])).astype('float32')

y_tr = np.asarray(df_tr['Rings']).astype('float32')

y_te = np.asarray(df_te['Rings']).astype('float32')

print(f"Size of training and test set: {df_tr.shape} | {df_te.shape}")

Size of training and test set: (3342, 11) | (835, 11)

The abalone dataset dimensions represent:

- 4,177 total samples: Split into 3,342 training and 835 test samples

-

11 features: Including both physical measurements and categorical data:

- Physical attributes (length, diameter, height, weights)

- Categorical sex information (encoded as one-hot vectors)

- Target variable: Number of rings (age indicator) to predict

An important step for any machine learning project is appropriate features scaling. Now, we could use something

like scipy or scikit-learn to do this task. But let’s see how this can also be done directly with

TensorFlow.

# Normalize data with a keras layer

normalizer = tf.keras.layers.Normalization(axis=-1)

# Train the layer to establish normalization parameters

normalizer.adapt(x_tr)

# Verify normalization parameters

print(f"Mean parameters:\n{normalizer.adapt_mean.numpy()}\n")

print(f"Variance parameters:\n{normalizer.adapt_variance.numpy()}")

Mean parameters:

[0.5240649 0.4077229 0.13945538 0.82737887 0.35884637 0.18079534

0.23809911 0.313884 0.3255536 0.36056268]

Variance parameters:

[0.01422794 0.00970037 0.00150639 0.23864637 0.04889446 0.0120052

0.01888644 0.21536086 0.21956848 0.23055716]

2. Model Creation

Unlike our previous tutorial where we used the Sequential API, here we’ll use TensorFlow’s Functional API. The Functional API provides several key advantages:

- Multiple Inputs/Outputs: Can handle multiple input/output streams

- Layer Sharing: Reuse layers across different parts of the model

- Non-Sequential Flow: Create models with branches or multiple paths

- Complex Architectures: Easily implement advanced patterns like skip connections

- Better Visualization: Clearer view of data flow between layers

Here’s how we build a model using the Functional API:

# Create layers and connect them with functional API

input_layer = keras.Input(shape=(x_tr.shape[1],))

# Normalize inputs using our pre-trained normalization layer

x = normalizer(input_layer)

# Build hidden layers with explicit connections

x = layers.Dense(8)(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x) # Stabilizes training

x = layers.ReLU()(x) # Non-linear activation

x = layers.Dropout(0.5)(x) # Prevents overfitting

# Second dense layer with similar structure but fewer neurons

x = layers.Dense(4)(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.ReLU()(x)

x = layers.Dropout(0.5)(x)

# Output layer for regression (no activation function)

output_layer = layers.Dense(1)(x)

# Create model by specifying inputs and outputs

model = keras.Model(inputs=input_layer, outputs=output_layer)

# Check model size

model.summary(show_trainable=False)

Model: "model"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

input_1 (InputLayer) [(None, 10)] 0

normalization (Normalizati (None, 10) 21

on)

dense (Dense) (None, 8) 88

batch_normalization (Batch (None, 8) 32

Normalization)

re_lu (ReLU) (None, 8) 0

dropout (Dropout) (None, 8) 0

dense_1 (Dense) (None, 4) 36

batch_normalization_1 (Bat (None, 4) 16

chNormalization)

re_lu_1 (ReLU) (None, 4) 0

dropout_1 (Dropout) (None, 4) 0

dense_2 (Dense) (None, 1) 5

=================================================================

Total params: 198 (796.00 Byte)

Trainable params: 153 (612.00 Byte)

Non-trainable params: 45 (184.00 Byte)

_________________________________________________________________

Notice how each layer is explicitly connected using function calls (e.g., layers.Dense(8)(x)). This syntax makes the data flow clear and allows for complex branching patterns that aren’t possible with the Sequential API.

Now that the model is ready, let’s go ahead and compile it. During this process we can specify an appropriate optimizer as well as relevant metrics that we want to keep track of.

# Compile model

model.compile(

optimizer=keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=1e-3),

loss=keras.losses.MeanSquaredError(name='MSE'),

metrics=[keras.metrics.MeanAbsoluteError(name='MAE')],

)

Before we move over to training the model, let’s first create a few useful callbacks. Callbacks are powerful tools that can:

- Save the best model during training

- Stop training early if no improvement is seen

- Adjust learning rate dynamically

- Log training metrics for later analysis

These callbacks can be used to perform some interesting tasks before, during or after a batch, an epoch or training in general. We’ll implement several of these to create a robust training pipeline.

# Save best performing model (based on validation loss) in checkpoint

model_checkpoint_callback = keras.callbacks.ModelCheckpoint(

filepath='model_backup',

save_weights_only=False,

monitor='val_loss',

mode='min',

save_best_only=True,

verbose=0,

)

# Store training history in csv file

history_logger = keras.callbacks.CSVLogger(

'history_log.csv', separator=',', append=False

)

# Reduce learning rate on plateau

reduce_lr_on_plateau = (

keras.callbacks.ReduceLROnPlateau(

monitor='val_loss', factor=0.1, patience=10, min_lr=1e-5, verbose=0

),

)

# Use early stopping to stop learning once it doesn't improve anymore

early_stopping = (

keras.callbacks.EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', patience=20, verbose=1),

)

3. Training

The data is ready, the model is setup - we’re good to go!

# Train model

history = model.fit(

x=x_tr,

y=y_tr,

validation_split=0.2,

shuffle=True,

batch_size=64,

epochs=200,

verbose=1,

callbacks=[

model_checkpoint_callback,

history_logger,

reduce_lr_on_plateau,

early_stopping,

],

)

Epoch 1/200

42/42 [==============================] - 2s 36ms/step - loss: 110.4277 - MAE: 9.9720 - val_loss: 104.8957 - val_MAE: 9.7636 - lr: 0.0010

Epoch 2/200

42/42 [==============================] - 1s 29ms/step - loss: 106.3978 - MAE: 9.7741 - val_loss: 101.7641 - val_MAE: 9.6255 - lr: 0.0010

Epoch 3/200

42/42 [==============================] - 1s 29ms/step - loss: 102.8426 - MAE: 9.5989 - val_loss: 99.2429 - val_MAE: 9.5080 - lr: 0.0010

...

Epoch 199/200

42/42 [==============================] - 0s 8ms/step - loss: 9.5845 - MAE: 2.2097 - val_loss: 6.4356 - val_MAE: 1.7255 - lr: 0.0010

Epoch 200/200

42/42 [==============================] - 0s 8ms/step - loss: 8.9521 - MAE: 2.1254 - val_loss: 6.4109 - val_MAE: 1.7223 - lr: 0.0010

Once the model is trained we can go ahead and investigate performance during training. Instead of using the

history variable, let’s load the same information from the CSV saved by the checkpoint.

def plot_history(history_file='history_log.csv', title=''):

# Load training history from CSV

history_log = pd.read_csv(history_file)

# Create subplots for loss and MAE metrics

_, axs = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 4))

# Plot loss metrics

history_log.iloc[:, history_log.columns.str.contains('loss')].plot(

title="Loss during training", ax=axs[0]

)

# Plot MAE metrics

history_log.iloc[:, history_log.columns.str.contains('MAE')].plot(

title="MAE during training", ax=axs[1]

)

# Configure axis labels and scales

axs[0].set_ylabel("Loss")

axs[1].set_ylabel("MAE")

for idx in range(len(axs)):

axs[idx].set_xlabel("Epoch [#]")

axs[idx].set_yscale('log') # Use log scale for better visualization of changes

plt.suptitle(title, fontsize=14)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Plot training history

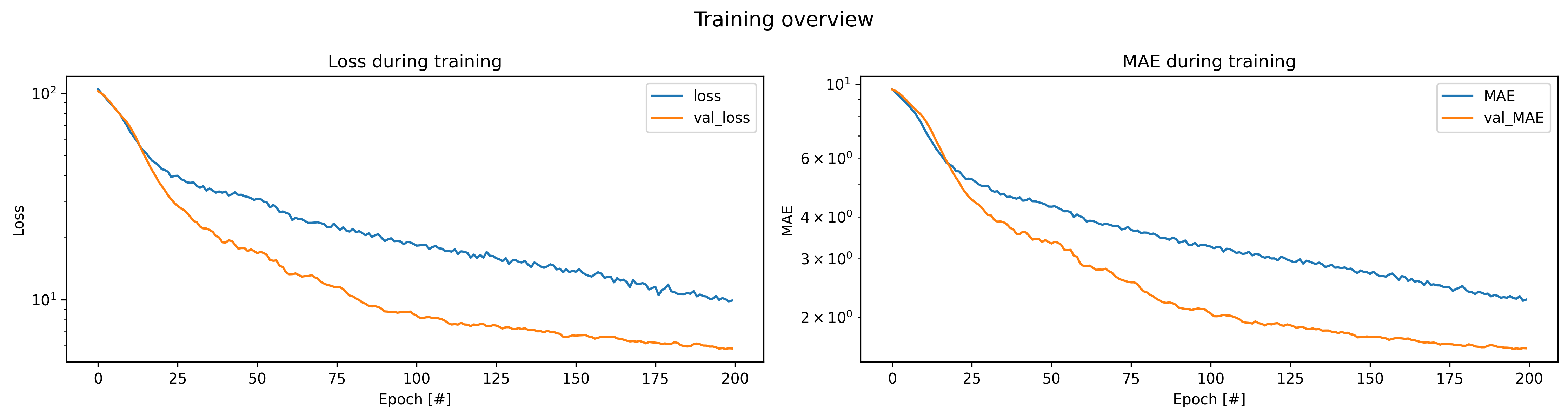

plot_history(history_file='history_log.csv', title="Training overview")

Analyzing Model Performance

Let’s examine our model’s performance from multiple angles:

- Training history to check for overfitting

- Prediction accuracy across different value ranges

- Feature importance through a sensitivity analysis

- Comparison with simpler baseline models

This multi-faceted analysis helps us understand both where our model succeeds and where it might need improvement.

Looking at the training history above, we can see that:

- The model converges smoothly without major fluctuations

- Validation metrics closely follow training metrics, suggesting no significant overfitting

- Both MSE and MAE show consistent improvement throughout training

4. Inference

The model training seems to have worked well. Let’s now go ahead and test the model. For this, let’s first load the best model - saved by the callback during training. This doesn’t need to be the same as the model at the end of the training.

# Load best model

model_best = keras.models.load_model('model_backup')

# Evaluate best model on test set

train_results = model_best.evaluate(x_tr, y_tr, verbose=0)

test_results = model_best.evaluate(x_te, y_te, verbose=0)

print("Train - Loss: {:.3f} | MAE: {:.3f}".format(*train_results))

print("Test - Loss: {:.3f} | MAE: {:.3f}".format(*test_results))

Train - Loss: 6.264 | MAE: 1.696

Test - Loss: 7.393 | MAE: 1.778

Let’s break down these final performance metrics:

-

Training Metrics:

- Loss (6.264): Measures overall prediction error

- MAE (1.696): Average deviation of ~1.7 rings in age predictions

-

Test Metrics:

- Loss (7.393): ~18% higher than training, indicating some overfitting

- MAE (1.778): Predictions off by ~1.8 rings on average

- Practical Impact: For abalone age prediction, being off by less than 2 rings is acceptable for most applications

5. Architecture fine-tuning

Let’s now go a step further and create a setup with which we can fine-tune the model architecture. While there are different frameworks, such as KerasTuner or Sci-Kears - let’s perform a more manual approach.

For this we need two things: First, a function that creates the model and sets the compiler, and second a parameter grid.

Function to dynamically create a model

def build_and_compile_model(

hidden=[8, 4], # List defining sizes of hidden layers

activation='relu', # Activation function for hidden layers

use_batch=True, # Whether to use batch normalization

dropout_rate=0, # Dropout rate for regularization

learning_rate=0.001, # Initial learning rate

optimizers='adam', # Choice of optimizer

kernel_init='he_normal', # Weight initialization strategy

kernel_regularizer=None, # Weight regularization method

):

# Create input layer

input_layer = keras.Input(shape=(x_tr.shape[1],))

# Normalize input data

x = normalizer(input_layer)

# Build hidden layers

for idx, h in enumerate(hidden):

# Add batch normalization if requested

if use_batch:

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

# Add dense layer with specific parameters

x = layers.Dense(

h,

activation=activation,

kernel_initializer=kernel_init,

kernel_regularizer=kernel_regularizer,

)(x)

# Add dropout layer if requested

if dropout_rate > 0:

x = layers.Dropout(dropout_rate)(x)

# Add output layer (no activation for regression)

output_layer = layers.Dense(1)(x)

# Create and compile model

model = keras.Model(inputs=input_layer, outputs=output_layer)

# Configure optimizer based on selection

if optimizers == 'adam':

optimizer = keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=learning_rate)

elif optimizers == 'rmsprop':

optimizer = keras.optimizers.RMSprop(learning_rate=learning_rate)

elif optimizers == 'sgd':

optimizer = keras.optimizers.SGD(learning_rate=learning_rate, nesterov=True)

# Compile model with loss and metrics

model.compile(

optimizer=optimizer,

loss=keras.losses.MeanSquaredError(name='MSE'),

metrics=[keras.metrics.MeanAbsoluteError(name='MAE')],

)

return model

# Use function to create model and report summary overview

model = build_and_compile_model()

model.summary()

Model: "model_1"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

input_2 (InputLayer) [(None, 10)] 0

normalization (Normalizati (None, 10) 21

on)

batch_normalization_2 (Bat (None, 10) 40

chNormalization)

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 8) 88

batch_normalization_3 (Bat (None, 8) 32

chNormalization)

dense_4 (Dense) (None, 4) 36

dense_5 (Dense) (None, 1) 5

=================================================================

Total params: 222 (892.00 Byte)

Trainable params: 165 (660.00 Byte)

Non-trainable params: 57 (232.00 Byte)

_________________________________________________________________

Next step is the creation of the parameter grid. First, let’s establish the different parameters we could explore.

# Define exploration grid

hidden = [[8], [8, 4], [8, 16, 8]]

activation = ['relu', 'elu', 'selu', 'tanh', 'sigmoid']

use_batch = [False, True]

dropout_rate = [0, 0.5]

learning_rate = [1e-3, 1e-4]

optimizers = ['adam', 'rmsprop', 'sgd']

kernel_init = [

'he_normal',

'he_uniform',

'glorot_normal',

'glorot_uniform',

'uniform',

'normal',

]

kernel_regularizer = [None, 'l1', 'l2', 'l1_l2']

batch_sizes = [32, 128]

Now, let’s put all of this into a parameter grid.

# Create parameter grid

param_grid = dict(

hidden=hidden, # Network architectures from simple to complex

activation=activation, # Different non-linearities for different data patterns

use_batch=use_batch, # Batch normalization for training stability

dropout_rate=dropout_rate, # Regularization to prevent overfitting

learning_rate=learning_rate, # Controls step size during optimization

optimizers=optimizers, # Different optimization strategies

kernel_init=kernel_init, # Weight initialization methods

kernel_regularizer=kernel_regularizer, # Weight penalties to prevent overfitting

batch_size=batch_sizes, # Training batch sizes for different memory/speed tradeoffs

)

# Go through the parameter grid

from sklearn.model_selection import ParameterGrid

grid = ParameterGrid(param_grid)

print(f"Exploring {len(grid)} network architectures.")

Exploring 17280 network architectures.

Ok… these are definitely too many grid points. So let’s shuffle the grid and explore a few iterations to get a better sense of what works and what doesn’t.

# Number of grid points to explore

nth = 5

# Establish grid indecies, shuffle them and keep the first N-th entries

grid_idx = np.arange(len(grid))

np.random.shuffle(grid_idx)

grid_idx = grid_idx[:nth]

Now, we’re good to go!

# Loop through grid points

for gixd in grid_idx:

# Select grid point

g = grid[gixd]

print(f"Exploring: {g}")

# Build and compile model

model = build_and_compile_model(

hidden=g['hidden'],

activation=g['activation'],

use_batch=g['use_batch'],

dropout_rate=g['dropout_rate'],

learning_rate=g['learning_rate'],

optimizers=g['optimizers'],

kernel_init=g['kernel_init'],

kernel_regularizer=g['kernel_regularizer'],

)

# Save best performing model (based on validation loss) in checkpoint

backup_path = f'model_backup_{gixd}'

model_checkpoint_callback = keras.callbacks.ModelCheckpoint(

filepath=backup_path,

save_weights_only=False,

monitor='val_loss',

mode='min',

save_best_only=True,

verbose=0,

)

# Store training history in csv file

history_file = f'history_log_{gixd}.csv'

history_logger = keras.callbacks.CSVLogger(

history_file, separator=',', append=False

)

# Setup callbacks

callbacks = [

model_checkpoint_callback,

history_logger,

reduce_lr_on_plateau,

early_stopping,

]

# Train model

history = model.fit(

x=x_tr,

y=y_tr,

validation_split=0.2,

shuffle=True,

batch_size=g['batch_size'],

epochs=200,

callbacks=callbacks,

verbose=0

)

# Load best model

model_best = keras.models.load_model(backup_path)

# Evaluate best model on test set

train_results = model_best.evaluate(x_tr, y_tr, verbose=0)

test_results = model_best.evaluate(x_te, y_te, verbose=0)

print("\tTrain - Loss: {:.3f} | MAE: {:.3f}".format(*train_results))

print("\tTest - Loss: {:.3f} | MAE: {:.3f}".format(*test_results))

print(f"\tModel Parameters: {model.count_params()}\n\n")

Exploring: {'use_batch': False, 'optimizers': 'sgd', 'learning_rate': 0.0001,

'kernel_regularizer': None, 'kernel_init': 'glorot_uniform', 'hidden': [8],

'dropout_rate': 0, 'batch_size': 128, 'activation': 'selu'}

Train - Loss: 5.294 | MAE: 1.643

Test - Loss: 7.148 | MAE: 1.807

Model Parameters: 118

Exploring: {'use_batch': False, 'optimizers': 'sgd', 'learning_rate': 0.001,

'kernel_regularizer': None, 'kernel_init': 'glorot_uniform', 'hidden': [8, 4],

'dropout_rate': 0.5, 'batch_size': 128, 'activation': 'tanh'}

Train - Loss: 5.290 | MAE: 1.583

Test - Loss: 6.250 | MAE: 1.730

Model Parameters: 150

Exploring: {'use_batch': True, 'optimizers': 'sgd', 'learning_rate': 0.0001,

'kernel_regularizer': None, 'kernel_init': 'uniform', 'hidden': [8, 4],

'dropout_rate': 0.5, 'batch_size': 32, 'activation': 'relu'}

Epoch 195: early stopping

Train - Loss: 8.660 | MAE: 2.050

Test - Loss: 10.039 | MAE: 2.144

Model Parameters: 222

Exploring: {'use_batch': True, 'optimizers': 'rmsprop', 'learning_rate': 0.0001,

'kernel_regularizer': None, 'kernel_init': 'he_uniform', 'hidden': [8, 16, 8],

'dropout_rate': 0.5, 'batch_size': 128, 'activation': 'tanh'}

Train - Loss: 24.535 | MAE: 3.957

Test - Loss: 26.605 | MAE: 4.079

Model Parameters: 534

Exploring: {'use_batch': False, 'optimizers': 'adam', 'learning_rate': 0.0001,

'kernel_regularizer': 'l2', 'kernel_init': 'glorot_uniform', 'hidden': [8, 16, 8],

'dropout_rate': 0.5, 'batch_size': 128, 'activation': 'selu'}

Train - Loss: 6.947 | MAE: 1.715

Test - Loss: 8.042 | MAE: 1.851

Model Parameters: 398

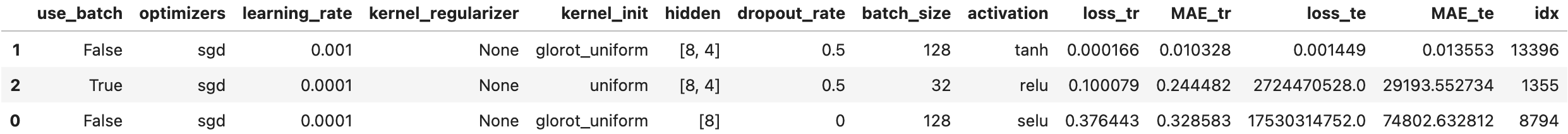

6. Fine-tuning investigation

Once the grid points were explored we can go ahead and investigate the best models.

results = []

# Loop through grid points

for gixd in grid_idx:

# Select grid point

g = grid[gixd]

# Restore best model

backup_path = f'model_backup_{gixd}'

model_best = keras.models.load_model(backup_path)

# Evaluate best model on test set

train_results = model_best.evaluate(x_tr, y_tr, verbose=0)

test_results = model_best.evaluate(x_te, y_te, verbose=0)

# Store information in table

df_score = pd.Series(g)

df_score['loss_tr'] = train_results[0]

df_score['MAE_tr'] = train_results[1]

df_score['loss_te'] = test_results[0]

df_score['MAE_te'] = test_results[1]

df_score['idx'] = gixd

results.append(df_score.to_frame().T)

results = pd.concat(results).reset_index(drop=True).sort_values('loss_te')

results

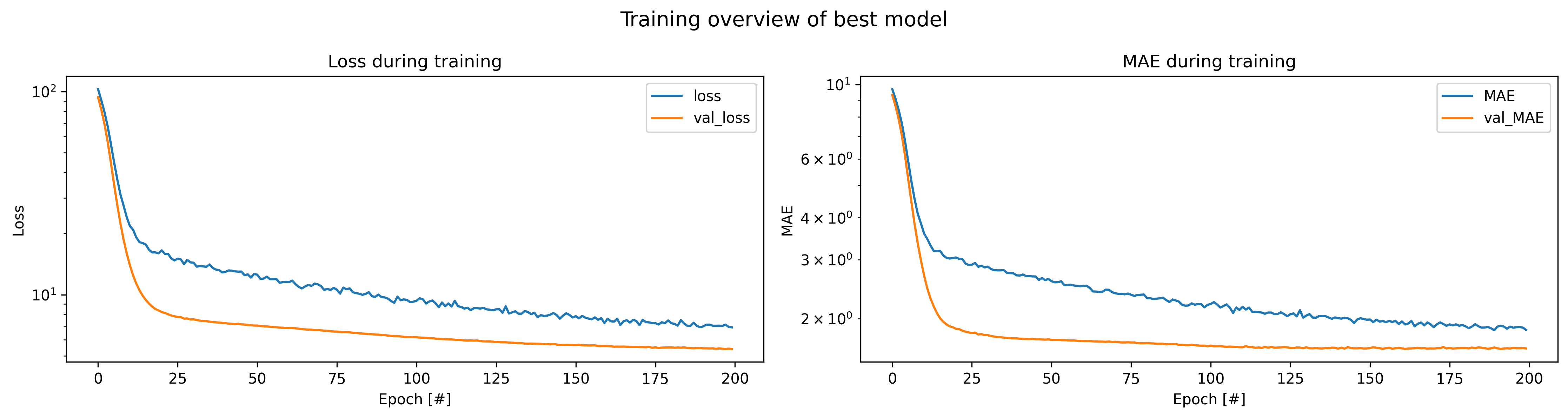

From this table, you could now perform a multitude of follow-up investigations. For example, take a look at the loss evolution during training:

# Get idx of best model

gixd_best = results.iloc[0, -1]

# Load history file of best training

history_file = f'history_log_{gixd_best}.csv'

# Plot training curves

plot_history(history_file=history_file, title="Training overview of best model")

Advanced Deep Learning Pitfalls

When working with complex neural networks and regression tasks, be aware of these advanced challenges:

Gradient Issues

- Vanishing/exploding gradients in deep networks

- Unstable training with certain architectures

# Use gradient clipping to prevent explosions

optimizer = keras.optimizers.Adam(

clipnorm=1.0,

learning_rate=1e-3

)

# Add batch normalization to help with gradient flow

x = layers.Dense(64)(inputs)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.ReLU()(x)

Learning Rate Dynamics

- Static learning rates often suboptimal

- Different layers may need different rates

# Implement learning rate schedule

initial_learning_rate = 0.1

decay_steps = 1000

decay_rate = 0.9

lr_schedule = keras.optimizers.schedules.ExponentialDecay(

initial_learning_rate,

decay_steps=decay_steps,

decay_rate=decay_rate

)

# Or use adaptive learning rate with warmup

warmup_steps = 1000

def warmup_cosine_decay(step):

warmup_rate = initial_learning_rate * step / warmup_steps

cosine_rate = tf.keras.experimental.CosineDecay(

initial_learning_rate, decay_steps

)(step)

return tf.where(step < warmup_steps, warmup_rate, cosine_rate)

Complex Loss Functions

- Multiple objectives need careful weighting

- Custom losses require gradient consideration

- Handle edge cases and numerical stability

class WeightedMSE(keras.losses.Loss):

def __init__(self, feature_weights, **kwargs):

super().__init__(**kwargs)

self.feature_weights = tf.constant(feature_weights, dtype=tf.float32)

def call(self, y_true, y_pred):

# Add small epsilon to prevent numerical issues

y_pred = tf.clip_by_value(y_pred, 1e-7, 1.0)

squared_errors = tf.square(y_true - y_pred)

weighted_errors = squared_errors * self.feature_weights

return tf.reduce_mean(weighted_errors, axis=-1)

Data Pipeline Bottlenecks

- I/O can become training bottleneck

- Memory constraints with large datasets

# Efficient data pipeline with prefetching

dataset = tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices((x_tr, y_tr))

dataset = dataset.shuffle(buffer_size=1024)

dataset = dataset.batch(32)

dataset = dataset.prefetch(tf.data.AUTOTUNE)

# For large datasets, use generators

def data_generator():

while True:

for i in range(0, len(x_tr), batch_size):

yield x_tr[i:i+batch_size], y_tr[i:i+batch_size]

Model Architecture Complexity

- Deeper isn’t always better

- Skip connections can help with gradient flow

# Example of residual connection

def residual_block(x, filters):

shortcut = x

x = layers.Conv2D(filters, 3, padding='same')(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.ReLU()(x)

x = layers.Conv2D(filters, 3, padding='same')(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.Add()([shortcut, x]) # Skip connection

return layers.ReLU()(x)

Regularization Strategy

- Different layers may need different regularization

- Combine multiple regularization techniques

# Comprehensive regularization strategy

x = layers.Dense(

64,

kernel_regularizer=keras.regularizers.l1_l2(l1=1e-5, l2=1e-4),

activity_regularizer=keras.regularizers.l1(1e-5)

)(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.Dropout(0.5)(x)

Model Debugging

- Add metrics to monitor internal states

- Use callbacks for detailed inspection

- Clear unused variables and models

# Clear memory after training experiments

import gc

def cleanup_memory():

# Delete unused variables

del unused_model

# Force garbage collection

gc.collect()

# Clear TensorFlow session

tf.keras.backend.clear_session()

# Monitor layer states during training

class LayerStateCallback(keras.callbacks.Callback):

def on_epoch_end(self, epoch, logs=None):

layer_outputs = [layer.output for layer in self.model.layers]

inspection_model = keras.Model(

inputs=self.model.input,

outputs=layer_outputs

)

# Monitor layer statistics during training

layer_states = inspection_model.predict(x_val[:100])

for layer_idx, states in enumerate(layer_states):

print(f"Layer {layer_idx} stats:",

f"mean={np.mean(states):.3f},",

f"std={np.std(states):.3f}")

# Clean up inspection model

del inspection_model

gc.collect()

These advanced considerations become crucial when:

- Working with complex architectures

- Training on large datasets

- Optimizing for specific performance metrics

- Deploying models in production environments

- Debugging training issues

Summary and Series Conclusion

In this final tutorial, we’ve covered:

- Building a regression model using TensorFlow’s functional API

- Implementing custom normalization layers

- Using callbacks for training optimization

- Comparing different model approaches

Key takeaways:

- Complex architectures aren’t always better

- Proper training procedures are crucial

- Model comparison helps choose the best approach

- Advanced features require careful tuning

- Different architectures suit different problems

Throughout this series, we’ve progressed from basic classification to advanced regression, covering both traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches. We’ve seen how Scikit-learn and TensorFlow complement each other, each offering unique strengths for different types of problems.

← Previous: Advanced Machine Learning or Return to Series Overview →